Translate this page into:

Herbal Products Sold in Sikkim Himalaya Region – India: A Mini Survey

*Corresponding author: Sonam Bhutia, Department of Pharmacognosy, Government Pharmacy College, Sajong, Government of Sikkim, Gangtok, Sikkim, India. sonamkzbhutia@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Bhutia KN, Basnett DK, Bhattarai A, Bhutia S. Herbal products sold in Sikkim Himalaya Region – India: A mini survey. Glob J Med Pharm Biomed Update 2023;18:14.

Abstract

Objective:

The present survey aimed to interact with the vendors, analyze, examine, and document the herbal medicinal products sold in retail stores, pharmacies, AYUSH stores, generally closed and open markets in the local area of Sikkim, mainly rural towns – Gangtok, Ranipool, Singtam, and Rangpo. It was a first of its kind study on the selected topic in Sikkim – India.

Material and Methods:

The methodology followed during the survey was a cross-sectional study, open ended semi-structured questionnaire, and survey data collection tools were employed; descriptive and inferential statistics were done.

Results:

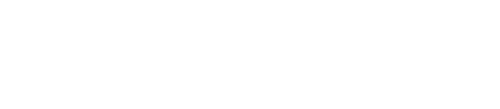

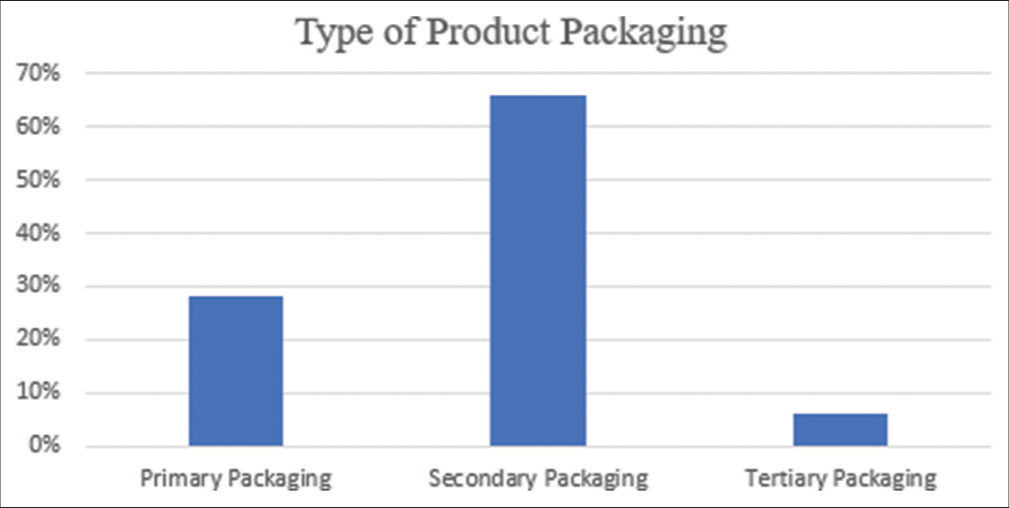

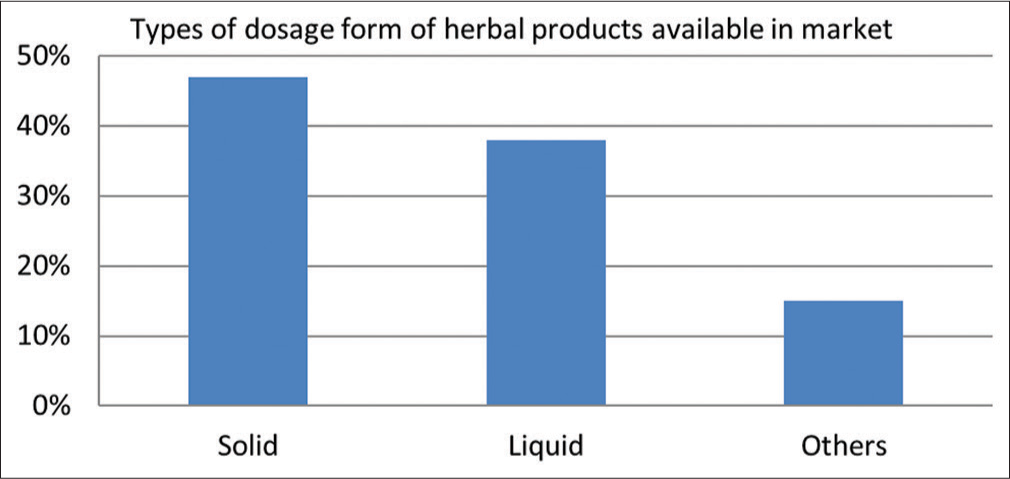

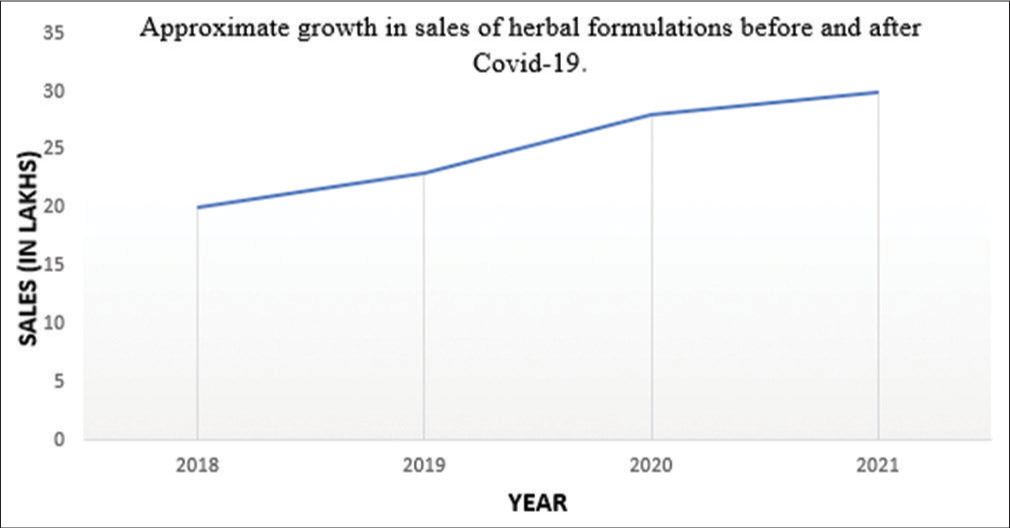

The results were summarized in the different tables. From, it was found that old age (46+) uses most of the herbal products (66.6%), adult (20–45 years) uses 42.6% of herbal products, adolescent (13–19) uses 16.6%, and child (1–12) uses 14.5%. Females use more herbal products than males at 57%, and males at 43%. It was found that a large number of herbal products in Sikkim are manufactured outside Sikkim (98%) and 2% of the products were manufactured in Sikkim. Herbal product packaging is mostly secondary (66%), followed by primary (28%) and tertiary packaging (6%). It was found that a large number of solid dosage (47%) form of herbal products is available in the market followed by liquid dosage form (38%). According to brand wise or company wise, Patanjali (41%) products accounted for a big share on the market followed by Baidyanath (19%), other brands (15%), AYUSH (11%), Himalaya (8%), and Dabur (6%). Based on diseases treated, digestion, and metabolism (21%) followed by bone and joint pain (17%), diabetes mellitus (14%), cough and cold (12%), piles (11%), hypertension (7%), thyroid (3%), and other other common diseases categories represents about 15%. Highlights the situation after the COVID-19 pandemic indicating drastic increases in market value (in Lakhs) and the sale of herbal products in Sikkim.

Conclusion:

The data highlighted above were the first of its kind in a study done in Sikkim – India; no data were available in any scientific repositories to date.

Keywords

Herbal medicines

Sikkim

Herbal products

Survey

Pilot study

INTRODUCTION

The use of natural medicines has significantly expanded globally. Global sales of herbal goods were expected to be $60 billion in US dollars in 2000, according to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.[1] About 75–80% of the world’s population mainly in developing countries still relies mostly on herbal medicine for primary healthcare, especially in underdeveloped nations.[2,3] The obesity epidemic, the prevalence of chronic illnesses and pain syndromes, anxiety and depression, the general desire for wellness and good health, disease prevention, the rising cost of conventional medications, and the traditional belief that complementary and alternative system of medicine (CAM) is safer and more effective than prescription medications that frequently have side effects are just a few of the factors contributing to the increased use of CAM. With more than 45,000 plant species, India is one of the 12 mega centers of biodiversity. Eight hundred plants have been employed in traditional medicine, while ancient literature list about 1500 different plants that have therapeutic uses. The gap between India and other nations in the field of herbs, however, is fast growing since India has failed to make an effect on the global market with pharmaceuticals made from plants.[4,5] The World Health Organization (WHO) states that herbal medicines are naturally occurring substances obtained from plants, are safer than synthetic compounds, However may cause bad effects if the wrong species, dose, or other factors are used incorrectly. Herbal medications and their formulations have been utilized in vast quantities for thousands of years because of their natural source and few adverse effects. The herbal medications are safe, inexpensive, and readily available (Ekor, 2014). According, to the WHO, the usage of herbal treatments is 2 to 3 times greater than that of conventional medications worldwide (Evans 1994) (WHO, 2019). Plants have been used for therapeutic reasons since the dawn of time, and much of contemporary medicine has its roots in this tradition.[6,7] In the middle of the 20th century, herbal remedies were abandoned for use in conventional medicine, not necessarily because they were unsuccessful but rather because they were less financially lucrative than the more recent synthetic pharmaceuticals (Tyler 1999).[8] As the risks and shortcomings of modern medicine have begun to become more obvious, there has been a trend toward the use of herbal therapy on a worldwide scale. Large quantities of Ayurvedic formulations are prepared from herbs.[9] The present survey was carried out to analyze the market of herbal products sold in Sikkim state – India by selecting the geographical locations, and major towns of Sikkim – Gangtok, Ranipool, Singtam, and Rangpo. The surveyors collected the data by interacting with the vendors, examining the different herbal products, and documentating the herbal medicinal products sold in retail stores, pharmacies, AYUSH stores, and generally closed and open markets in the local area of Sikkim. The state of Sikkim, has 7096 sq. km total area rich in flora and fauna diversity. The state is landlocked and shares borders – China-North, Nepal-West, and Bhutan-East and one state of India, the West Bengal-South state, The third highest mountain,-Mt. Kanchendzonga of Great Himalaya, makes Sikkim a unique inhabitable with a 6.1 lakh population (census-2011).[10] According to the Biodiversity Board, Government of Sikkim, there are 424 medicinal plants documented and utilized by the local community – Bhutia, Lepcha, and Nepali to treat their illnesses or disorders.[11] After the COVID-19 situation in Sikkim, it was observed that the local society were using herbal products in large quantities, not only in Sikkim-India but also globally.[12] Our survey focuses on the main impact of herbal products among the Sikkimese people by considering the following parameters-consumption, overall utility, product distribution based on open and closed markets, product preference, utility by age- and gender, highest product use, dosage forms, indication, disease condition, compositions, side effects, use of packaging, manufacturing and expiry date of the products, registration of the products (NAFDAC), annual turnover of the herbal products business, and perspective of the consumers toward the herbal products.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The methodology followed during the survey is highlighted below: Cross-sectional study, field survey, open-ended, and semi-structured questionnaire. We conducted this marketing survey on herbal products by personally meeting the herbal shop owners/shopkeepers and asking them about all the herbal medicine available in their shops. We also visited AYUSH Hospital and interacted with the staff of that hospital. We obtained the institutional approval letter for conducting this mini-pilot survey study: Meno No. 89/GPC/2022, and dated: May 10, 2022. It was part of a Bachelor of Pharmacy, 8th Semester 3–6-month mini project [Appendix 1].

Statistical analyses

The results are expressed as mean ± standard errors by the Excel software and the variance was studied by Student’s “t” test. The significance threshold was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The results were summarized in the different tables [Tables 1-3] and Figures [Figures 1-4] of the survey study above. [Table 1], shows that old age (46+) uses most of the herbal products (66.6%), adolescent (13–19) uses 16.6%, adult (20–45 years) uses 42.6%, and child (1–12) uses 14.5% of herbal products. As per the data collected for the use of herbal products based on gender, we found that females (57%) are using more herbs than males (43%). We also found that a large number of herbal products in Sikkim are manufactured outside Sikkim (98%) and only 2% of the products were manufactured in Sikkim. It might be due to geographical feasibilities, transportation facilities, more production units and suppliers are located outside Sikkim [Table 2]. Herbal products packaging mostly is secondary (66%), followed by primary (28%) and tertiary packaging (6%)-[Figure 1]. [Figure 2], shows that a large number of solid dosage (47%) forms of herbal products were available on the market followed by liquid dosage form (38%). Based on the availability of brands, Patanjali (41%) products were the most popular followed by Baidyanath (19%), other brands (15%), AYUSH (11%), Himalaya (8%) and Dabur (6%) [Figure 3]. Diseases treated using herbs are as follows:, digestion and metabolism (21%), bone and joint pain (17%), diabetes mellitus (14%), cough and cold (12%), piles (11%), hypertension (7%), thyroid (3%), and other categories (15%) [Table 3]. [Figure 4], highlights the situation after the COVID-19 pandemic when drastic increases in market value (in Lakhs) and the sale of herbal products in Sikkim were observed. The increase in the consumers of herbal products in Sikkim might be because of the easy access, cost-effectiveness, traditional beliefs, easy administration, and fewer side effects from herbs than synthetic products.

| S. No. | Age group | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Child (1–12 years) | 14.5 |

| 2. | Adolescent (13–19 years) | 16.6 |

| 3. | (Adult 20–45 years) | 42.6 |

| 4. | Old age (46+) | 66.6 |

| S. No. | Gender | Percentage |

| 1. | Male | 43 |

| 2. | Female | 57 |

| Manufacturing territory of products | Percentage (average) |

|---|---|

| Inside Sikkim | 2 |

| Outside Sikkim | 98 |

| S. No. | Category of disease | Percentage (average) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Digestion/metabolism | 21 |

| 2. | Bone and joint pain | 17 |

| 3. | Piles | 11 |

| 4. | Thyroid | 3 |

| 5. | Diabetes mellitus | 14 |

| 6. | Hypertension | 7 |

| 7. | Cough and cold | 12 |

| 8. | Others | 15 |

- The percentage of herbal products of product packaging.

- The percentage of types of dosage form of herbal products.

- The percentage of commonly available herbal brands in the market. *All the Herbal Products that are available at AYUSH are manufactured from Indian Medicines Pharmaceutical Corporation Limited (IMPCL). IMPCL or manufactured herbal products are available only at AYUSH Hospital and they are not for sale at commercial markets.

- Approximate growth in sales of herbal formulations before and after COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

According to the findings, the use of herbal products by older Sikkimese people is higher than that of other age groups. This situation may be due to traditional reasons and beliefs. As per the information collected about the use of herbal products based on gender, the females are using more products than males, and the reasons might be the traditional beliefs of women or mothers, fewer side effects of herbs than synthetics, holistic approach and easy preparation of herbal remedies.[13] The production or manufacture of the herbal products, was greater from outside Sikkim; only 2% of the herbal products were manufactured in Sikkim. The production of herbal products differs within the state due to location, transport facilities, distribution, presence of few vendors in Sikkim, lack of proper suppliers within the state, and geographical prospects means land formation, hilly terrains, etc. The most common herbal product packaging is secondary followed by primary and tertiary packaging. In terms of dosage form, the solid dosage form was more common than the other forms. This could be due to the advantages of solid dosage forms such as easy packaging, stability, accurate dosing, easy transportation, easy handling, easy storage, acceptability, and availability of dosages according to the requirements of patients, no need for special storage conditions and easy oral administration.[14,15]

CONCLUSION

Based on the data collection from the pilot study, it appeared that the use of herbal products or formulations had significantly increased in Sikkim before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The Sikkimese people are using the products to treat and to get relieve from their health issues for different diseases such as digestion/metabolism, bone and joint pain, piles, thyroid, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cough, and cold. From the survey, we found out that most of the herbal products got their the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration Control (NAFDC) registration. Some limitations were noticed during the survey, so there is need to educate Medicinal Plants and Traditional Treatment Practices (TMPs) on the essence of drug development. Herbal medicine producers must be further enlightened on enhancing the promotion and advertisement of the herbal products in the market. Medical sales representatives can be recruited to promote the herbal products in the market.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the host institute-Government Pharmacy College Sajong, Government of Sikkim for allowing us (B. Pharm, 8th Semester pharmacy undergraduate students) to do this mini-survey work mainly in the East district of Sikkim within the stipulated timeframe. Thanks to the entire college team.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standardization of some marketed herbal formulation used in diabetes. J Adv Res Pharm Sci Pharmacol Interv. 2018;2:22-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of herbal products and potential interactions in patients with cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:515-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A health risk assessment of lead and other metals in pharmaceutical herbal products and dietary supplements containing Ginkgo biloba in the Mexico city metropolitan area. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;18:8285.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of South African plants used for medicinal purposes. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;56:81-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbal medicine: Expanded Commission E Monograph Vol 133. United Kingdom: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International; 2000. p. :487.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herbal medication: Potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:391-401.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urgent conservation needs in the Sikkim Himalaya biodiversity hotspot. Biodiversity. 2019;20:88-97.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Some belief, practices and prospects of folk healers of Sikkim. Indian J Tradit Knowledge. 2012;11:369-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant Solutions for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Historical reflections and future perspectives. Mol Plant. 2020;13:803-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:177.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A benefit/risk approach towards selecting appropriate pharmaceutical dosage forms-an application for paediatric dosage form selection. Int J Pharm. 2012;435:115-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral drug delivery in personalized medicine: Unmet needs and novel approaches. Int J Pharm. 2011;404:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

APPENDIX

| Q1 What herbal products are available in your shop? Q2 What is the composition of the herbal product? Q3 Can you please explain the right route, right dose, and right time to use this herbal product? Q4 What is this product used for or for what category of disease is it used? Q5 What is the manufactory, expiry, and batch no. for this herbal product? Q6 Are there any contraindications? If “Yes”, What are they? Q7 What percentage of profit do you earn from the product? Q8 What are your sales before and after COVID-19? Q9 Is there a rise in the demand or sale of herbal products after COVID-19? Q10 Which is the herbal product commonly used by the patients? Q11 What is the approximate percentage sale of herbal products in your shop? Q12 Which age group mostly used herbal products? Q13 Which gender mostly used herbal products? Q14 Which products are purchased from Sikkim and which are ones come from outside Sikkim? Q15 What is the feedback from your customers regarding the herbal products? |