Gambling is betting something of value (usually money) on an event (usually a game) whose outcome is unpredictable or determined by chance1. It is a common leisure activity engaged in by many across cultures and countries. The large majority of gamblers do so without any harm coming upon themselves and on those around them. However for a minority, it can become problematic. Problem gambling is defined as gambling that disrupts or damages personal, family or recreational pursuits2. According to the ICD-103 diagnostic criteria, the essential diagnostic feature of pathological gambling is “persistently repeated gambling, which continues and often increases despite adverse consequences such as impoverishment, impaired family relationships and disruption of personal life.”

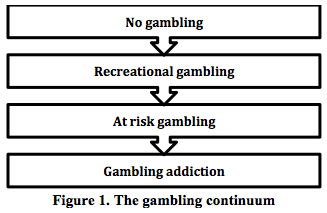

Akin to substance use, gambling too exists on a continuum ranging from non-gamblers to those who are gambling addicts (Figure 1). Gambling as an addiction has for the first time been included in the section on addictive disorders in DSM V, and this is the only non-substance addiction in that category.

Studies from the UK have shown that over 70% of adults in Britain had gambled at least once in the past 12 months and 0.9% were problem gamblers4. It was also interesting to note that 7.3% of those surveyed were deemed to be ‘at risk’ of developing a gambling problem in the future. International studies use various terms interchangeably such as gambling addiction, pathological gambling, problem gambling and so on, hence direct comparisons are difficult. However it would seem reasonable to conclude that general population prevalence rates for problematic gambling is in the region of 1 to 3%5.

Excessive gambling can adversely affect the gambler, his family and the wider society. It can impact on the gambler’s physical and psychological health. They often present with psychosomatic symptoms, and psychiatric comorbidity is very common (especially anxiety, depression and substance misuse). It can also lead to decreased job productivity, unemployment and involvement in crime. It can also lead to strained interpersonal relationships with family members and occasionally domestic violence.

Gambling addiction has a much higher prevalence rate among those seeking help from healthcare professionals. Studies have shown that 10% of primary care attendees and around 15% of those seeking help from mental health services, and up to 20% of those seeking treatment from substance misuse services have a co-existing gambling problem6. However more often than not most gamblers go undetected and hence un-helped. This is due to various reasons such as health professionals’ lack of awareness of the condition and patients’ own reluctance to disclose it. Hence, in our view, it is important for all doctors, whichever field of medicine they work in, to have basic knowledge of gambling addiction so they will know what to do if they come across a patient in their practice. This is the primary aim of this short paper editorial.

SCREENING

Most gamblers do not present to non-specialists seeking help for their gambling but instead have non-direct presentations such as insomnia, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, etc. Plus, many of them experience guilt and shame, hence do not disclose their gambling habit unless specifically asked. Hence we recommend that non-specialists enquire about this at least among their high risk patients such as those presenting with psychosomatic symptoms, other psychiatric disorders including substance misuse, depression and anxiety - spectrum disorders, those reporting financial problems, victims and perpetrators of domestic violence.

There are various screening questionnaires that can be used to screen for problem gambling7. We introduce one such screen, the Lie/Bet screen8. The Lie/Bet screen is a 2-question screening instrument; the questions are - 'Have you ever felt the need to bet more and more money?' and 'Have you ever had to lie to people important to you about how much you gamble?’ A positive response to either question identifies a pathological gambler, and it has a sensitivity of 0.99 and a specificity of 0.91, when compared to DSM - IV.

BRIEF INTERVENTIONS

Brief interventions are very short (5 to 10 minutes) psychological interventions that can be delivered by non-specialists in non-specialist settings. They were originally developed for use in patients misusing substances like alcohol but have since been shown to be effective in gamblers as well. The logic of brief intervention is that it prevents the progression of an addictive disorder (Figure 1).

We are not suggesting that all doctors need to be well versed with brief intervention for gambling but where resources (skills and time) permit it may be feasible. It is also worth remembering that the underlying principles are very similar to that of brief intervention for those with a drink problem. A brief gambling intervention model developed by Petry6 is described here. It consists of three steps. In the first step, the concept of the gambling continuum and the meaning of these different terms are explained. In the second step, the various harms associated with problem gambling are discussed, including financial harms, family harms, health harms and negative impact on work. In step three, simple and practical measures to reduce gambling are discussed such as putting limits on the amount of money spent on gambling, cutting down the time and days spent gambling, identifying non-gambling leisure activities, etc.

TREATMENT

Treatments available for problem gambling can be either pharmacological or psychological.

Although various pharmacotherapies have been tried to treat problem gamblers (including mood stabilizers, SSRIs, opiate antagonists and antipsychotics) no drug has so far been licensed for use in the UK or USA. Hence clinicians should only use pharmacotherapy to treat psychiatric comorbidity such as depression, anxiety, etc.

Hence psychotherapy remains the mainstay of treating problem gamblers and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is the most commonly used9. CBT includes cognitive and behavioural strategies. Gambling addicts have various cognitive distortions such as illusions of control, overestimates of one’s chances of winning, biased memories, etc. The underlying premise here is that as gambling is essentially about judging the probability of outcomes and decision making, it follows that cognitive distortions will lead to impaired judgement and poor decision making. CBT aims to address these cognitive distortions and, through functional analysis of gambling triggers, helps manage them and cope with cravings.

Those with gambling problems are best treated in specialist gambling treatment services if such services exist. If not, these patients are best referred to the more generic addiction (drugs and alcohol) services. Please check with the local addiction service as the first port of call. There is also Gamblers Anonymous (GA). GA is a 12-step fellowship and self-help modelled on Alcoholics Anonymous. It sees total abstinence from gambling as the aim/goal of treatment. GA also run support groups for families and friends affected by their loved one's gambling (Gam-Anon).

CONCLUSION

In our view it is useful for all healthcare professionals to be aware of gambling addiction as an addictive disorder that they may come across in their patients. It will be of added benefit if doctors know what to do to help a gambler.

REFERENCES

- Ladouceur R, Silvain C, Boutin C, Doucet, C. Understanding and Treating the Pathological Gambler. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. 2002.

- Lesieur HR, Rosenthal MD. Pathological gambling: A review of the literature (prepared for the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on DSM-IV Committee on disorders of impulse control not elsewhere classified). J Gambling Studies. 1991;7(1):5-39.

- World Health Organization. The ICD–10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines, Geneva. 1992.

- Wardle H, Moody A, Spence S, Orford J, et al. British Gambling Prevalence Survey. National Centre for Social Research. London: The Stationery Office. 2010.

- Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the US and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1369-76.

- Petry NM. Pathological Gambling: Etiology, Comorbidity and Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2005.

- Problem Gambling Research and Treatment Centre (PGRTC). Guideline for screening, assessment and treatment in problem gambling. Clayton: Monash University. 2011.

- Johnson EE, Hamer R, Nora RM, Tan B, et al. The Lie/Bet Questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychol Rep. 1997;80(1):83-8.

- Hodgins DC, Petry NM. Cognitive and behavioural treatments. In Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Edited by Grant JE, Potenza MN. Washington, DC: APPI. 2004.

Dr Sanju George

Associate Editor

Email: Sanju.george@bsmhft.nhs.uk